I think the greatest masters go on to achieve a kind of selflessness.

— Paul Graham, Hackers & Painters (O’Reilly Media, 2004)

The best companies of a few decades ago were like good employees. You know the type. You can count on them to be pleasant, to do one thing well, to play their part, and to stay in their lane—“lane keepers” you might say. But the good employee is not a great business builder. And the best companies of the past—like Adidas, Anheuser-Busch, Coca Cola, Diageo, GM, HSBC, IBM, McDonald’s, Schibsted, 3M, Toyota, Unilever, Wells Fargo, and even Walmart—rarely veered out of their lanes.

Today’s best companies, on the other hand, were born as full-on “wall breakers.” And they continue to break down more walls. Amazon, for example, went from ecommerce, to logistics, to software, to entertainment. It uses the expertise gained in each category to add more value for customers in other areas. Furthermore, it converts customers into partners, who become creators by offering reviews, launching their own stores, creating entertaining content, and developing their own software. Amazon keeps building flywheels that expand its offerings and improve their quality constantly. As a result, it meets a growing number of needs for customers, saving them precious time and mental energy for other experiences.

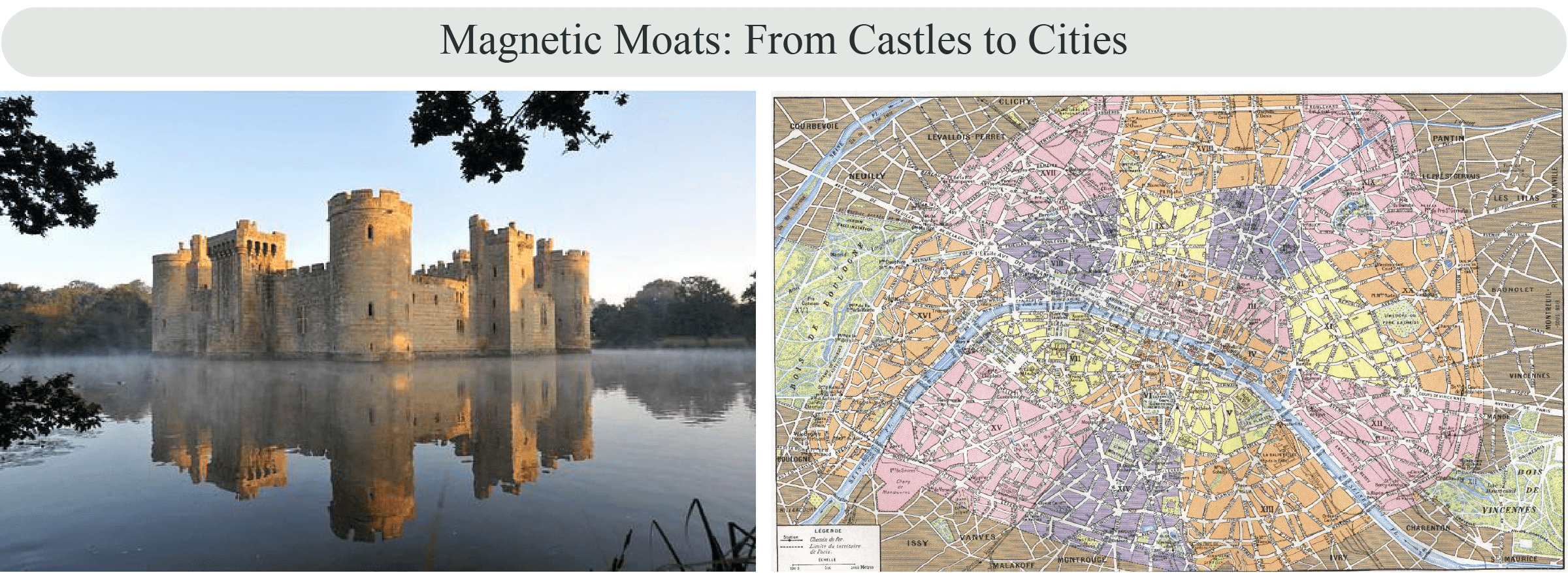

The compounding value of wall breakers across traditional barriers—whether category, geographic, or demographic—is a threat to traditional business moats. Even moats that once seemed secure—such as Walmart’s—are being challenged digitally by new businesses through platform ecosystems with creative tool sets, marketplaces, and app stores.

Limitless Compounding is Natural

The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process.

— Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (Harper & Brothers, 1950)

As demonstrated by the historical march from commodities, to manufactured goods, to consumables, and then to services, customers want better solutions and experiences rather than just materials. And each more efficient and higher quality solution opens up new growth paths that weren’t available to earlier iterations. The best companies have always compounded their offerings atop existing solutions, expanding their own runways while stunting the growth and return opportunities for laggards.

Today’s best companies have demonstrated that this process of “creative destruction”—previously experienced at the overall economy level through the competition between firms in each category—can now be accomplished within a single company even across multiple categories. The lesson for every company is clear: leverage your existing strengths and disrupt your past mindsets or face external disruption.

Limitless Compounding is Required

In order to insource “creative destruction,” today’s best businesses are disrupting old mindsets and products to fulfill customer needs at a pace that the old lane keepers could not even imagine.

All along the way, Larry and Sergey were consistent in their inconsistency with typical business principles. Given the choice between user delight and money, they went with user delight 100 percent of the time. It’s the reason we didn’t wind up at my level of 10 million users. Instead, Google Maps and Google Earth wound up at the level of 1 billion users. Monthly.

— Bill Kilday, Never Lost Again (HarperCollins, 2018)

Because doing more is proven to be possible, it is therefore also required. This axiom—demanded both by customer expectations and competitive realities—is being defined, and its limits tested, by the wall breakers. In addition to the largest tech companies, many others are building a range of services across multiple categories, including communication, entertainment, commerce, software, logistics, and financial. Stripe is publishing books and sees its mission as growing the GDP of the entire internet. TikTok is building a digital mall on top of its snappy videos. Next up may be any number of organic and inorganic possibilities that may have seemed absurd in prior times. Should Walmart enter gaming and also buy Netflix? Will Roblox merge with Discord and Snapchat? Will PayPal or Square buy eBay? Or will Sea Limited buy PayPal first? Should Spotify combine with Peloton? And should Disney acquire Booking.com, Live Nation, or Hilton?

Some of the most ambitious managements of traditional companies are fully aware of both the limitless opportunities that modern technologies enable and the mindset shift that today’s demanding customers and agile competitors require. In order to continue compounding customer value (CXC), they are also making bold moves to break the walls that were limiting their ability to adapt and innovate. The new Microsoft—which we discuss below—has done just this. The result, so far, is a $2.2tn increase in its market cap, or a 31% annual return during Satya Nadella’s tenure as CEO.

Now that each company must do more, each management team faces the conundrum of focus. How do you decide between expanding to new areas and sticking with your existing core? How does a company redefine its core? Which innovations and objectives should be prioritized? Answers to these questions inform the millions of decisions that companies like Amazon, DoorDash, Google, and Microsoft make daily. And because we are part owners of these businesses, the answers also inform our daily time- and capital-allocation decisions.

Financial Karma: The Principle of the First Customer

It’s important not just that the axioms be well chosen, but that there be few of them.

— Paul Graham, Hackers & Painters (O’Reilly Media, 2004)

We believe the timeless principle of karma—or its Western corollary, the golden rule—can help resolve the conundrum of where to focus. It’s simple: do for others what you want for yourself. And it works in perfect symmetry. Want to compound value sustainably for yourself? Do it for your customers.

Since a business starts with the first customer, every incremental action must improve value for this initial cohort of one. Companies must then improve value for each subsequent customer in ways that also add incremental value for the first customer. This is rule #1: the principle of the first customer.

The first customer wants a company to grow only when such growth benefits her. The customer doesn’t care whether this is done through economies of scale, network effects, improved agility, better feedback loops, faster execution, or bureaucracy-busting internal initiatives. She has plenty of other great choices. She just cares about improvement.

Hence, the clearest sign of a company that deserves to grow is one that can deliver limitless CXC to its first customer. The best founders understand this, while most professional managements, boards, and investors find it difficult to resist other temptations and distractions.

The Founders’ Ambition: Limitless CXC for the First Customer

We’ve had three big ideas at Amazon that we’ve stuck with for 18 years, and they’re the reason we’re successful: Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient.

— Jeff Bezos, founder-Chairman of Amazon, “Jeffrey Bezos, Washington Post’s Next Owner, Aims for a New ‘Golden Era’ at the Newspaper,” by Paul Farhi, Washington Post, September 3, 2013

It is incredibly powerful if you solve the problem you actually have yourself. It’s really tough to develop a good product when you don’t have very close proximity to the people who actually use the product. The closest proximity you can have to those people is to be that person.

— Tobias Lütke, founder-CEO of Shopify, “How Shopify Became the Go-To Ecommerce Platform for Startups,” by Katherine Duncan, Entrepreneur.com, March 13, 2012

The best founders’ ambition to compound value for their first customer comes from ground-level personal experience of the full depth and breadth of their customer’s problems. Some founders—like Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs, Pony Ma, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg—have a limitless mindset from the start; they begin with a view of endless opportunities to improve value for their first customers. Others grow into this mindset, such as Satya Nadella, the effective founder of the new Microsoft.

As a company grows, the best founders remain connected to their first customer—whether that was Sam Walton walking the aisles or Jeff Bezos taking support calls. The resulting solutions are innovative partly because they are embedded in solving the customer’s problems rather than competing for more market share. And the commitment to solving problems is so deep that founders naturally yearn to harness the energy of others through partnerships, both internally and externally.

Execution is the real-world bridge between scarce resources and a limitless, first-customer mindset. As Jeff Bezos already understood in drafting Amazon’s very first employee job post, to achieve non-linear results you require non-linear talent that can build non-linear business models.

You must have experience designing and building large and complex (yet maintainable) systems, and you should be able to do so in about one-third the time that most competent people think possible.

— Jeff Bezos, founder-Chairman of Amazon, job description for Amazon’s very first employee, by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr, Working Backwards (St. Martin’s Press, 2021)

Digital Scaling: More “No-Brainers” for More Customers

Change has to be fundamental to a company’s culture, or there is no way it can survive.

— Tobias Lütke, founder-CEO of Shopify

The internet has accelerated the pursuit of limitless value for the first customer. Digital technologies enable operational visibility and executional rigor that enhance economies of scale and disrupt the many bureaucratic and quality-zapping diseconomies of scale. With modern data analytics, if a division, region, or product is slipping in its value for customers, the board and management are no longer caught unaware. Also, they can no longer believe that there is any external barrier to their progress. This digital step-up in transparency and executional agility enables the creation of “no brainer” propositions that require no tradeoffs for the customer among convenience, quality, and price.

Digital technologies have also helped to better align corporate and customer interests. The very reality of a transparent relationship with immediate feedback loops and the possibility of a relationship that could either break immediately or last endlessly improves alignment. The enlightened company knows that both the customer’s endless carrot and sharp stick provide the clear incentive for it to harness the scale, feedback, network, and other benefits from each incremental customer to benefit all customers.

Companies that become ever-more of a “no-brainer” decision for their first customers can then bring these prioritization and execution playbooks to each subsequent customer-, creator- and product-type. Gradually and granularly, these companies build a layer cake of value across dimensions, becoming ever more magnetic for a broad range of customers and use cases. These customers come to expect the easy access of a neighborhood convenience store but with complex capabilities equivalent to having an Amazon warehouse in the basement. The clearest sign of companies building such easy-yet-robust solutions is both mass appeal and a range of customers and partners who spend and earn anywhere from $100 to $1bn+ per annum. In short, more customers, more creators, more merchants, and more revenues for and from each.

Open Metropolises: Accelerating the Path to Magnetic Ecosystems

When we first started monday.com, we started it with a mission: to give our customers the power to create their own work software. To do that, we revolutionized the way people use software, giving them the same abilities once reserved for software creators and designers. . . . As the number of our customers grew, we heard more and more stories of how we changed their businesses, and for some, their lives. We began to feel an ever-growing sense of responsibility—a responsibility to be there for our customers with world-class support and an ever-improving platform that allows them to do anything their business demands or their imagination takes them towards. We took that “no limits” approach to new heights when we opened up the platform completely for integrations to any other app or data source.

— Roy Mann and Eran Zinman, co-founders and co-CEOs of monday.com, “A Letter from Our Founders: monday.com is Now a Public Company,” monday.com blog, June 8, 2021

Today’s corporate metropolises began by solving for depth before breadth—building one service and then others, before gradually transitioning into platform ecosystems that combine inhouse solutions along with a broad range of creative third-party offerings. For example, Salesforce began as a simple no-brainer software solution for sales-centric enterprises and gradually grew—via its marketing, service, commerce, customization, integration, security, app store, and other capabilities—to become a no-brainer platform for all ambitious enterprises. As a result, its customers now include 90% of Fortune 500 companies.

Having learned the metropolis playbook, the fastest emerging companies are now evolving more quickly from essential services to metropolis business models. From the start, they are building to compound ownership density (COD) through connective platforms that harness the creative energy of their ecosystems. Shopify is a good example. Rather than try to build the best CRM, demand-generation engine, fulfillment network, payments service, or ERP software for every merchant, Shopify offers its customers an easy inhouse toolset and access to other services and channels for building digital and omni-commerce stores. From this central position, Shopify is prioritizing specific areas—most recently payments, fulfillment, global, and CRM capabilities—in which to build greater depth. Companies like Shopify are helping to further refine the metropolis playbook by using the breadth of their ecosystem to deepen their roots in critical services and vice versa.

What Shopify is doing for merchants, monday.com is doing for collaborative teams. Rather than attempt to build the most complex project management, CRM, word processing, integration, or automation tool, monday.com is focused on building the most seamless place for teams to coordinate, integrate, and automate across these and other tools. In other words, the company is prioritizing and curating to offer a simple gateway for a broad range of users to achieve a broad range of complex goals. Through this breadth, monday.com is honoring the core need for project management tools—they become more useful as they achieve broad and frequent usage within any team or organization.

Both Shopify and monday.com are modeling the spirit of an “open company,” reminding us of Paul Graham’s thoughts on open computing languages.

The [hacker’s] dream language is clean and terse. It has an interactive top level that starts up fast. You can write programs to solve common problems with very little code. Nearly all the code in any program you write is code that’s specific to your application. But everything else has been done for you. . . . The language is built in layers. . . . Nothing is hidden from you that doesn’t absolutely have to be. The language offers abstractions only as a way of saving you work rather than as a way of telling you what to do. In fact, the language encourages you to be an equal participant in its design. You can change everything about it, including even its syntax, and anything you write has, as much as possible, the same status as what comes predefined. The dream language is not only open source, but open design.

— Paul Graham, Hackers & Painters (O’Reilly Media, 2004)

The open company is built as a highly responsive, ownership-dense metropolis that hosts its customers’ own businesses, creativity, and identity. These easy, efficient, connected, and inviting platforms encourage customers to build their own SimCity-like presence, relationships, and workflows. Over time, we expect these platforms to become even more inviting for customers, creators, and businesses, partly by incorporating the most effective ideas that are emerging from the Web3 movement of blockchain, crypto, and beyond.

In addition to Shopify and monday.com, other open metropolises are emerging across categories. These include DoorDash for convenience, HubSpot for mid-market CRM, Roblox for gaming, Snowflake for data activation, Tegus for primary research, UiPath for multifactor automation, and Workato for API-based automation. Furthermore, customer and competitive dynamics are encouraging other, previously more limited companies—like Okta for identity and access management, DataDog for developers, and Atlassian and ServiceNow for IT workflows—to learn and implement the open metropolis playbook. Each of these companies is learning how to use the first-customer mindset to resolve the conundrum of focus as they pursue the full breadth and depth of their many opportunities.

Converting Corporate Castles to Magnetic Ecosystems

When we’re going to talk with Satya, we pull up the dashboards and we show him all the usage metrics. What’s the growth in the last seven days? What’s the growth of the last month? What are people using? What are they not using? It’s all grounded one hundred percent in the customer.

— Brad Anderson, CVP of enterprise client and mobility at Microsoft, “How an Obsession with Customers Made Microsoft a Two-Trillion Dollar Company,” by Steve Denning, Forbes, June 25, 2021

We believe Microsoft is the poster child of an old company learning the new ways. CEO Satya Nadella began by breaking down walls within and across departments, through its products, its attitude toward customers, its all-encompassing business model, and even partnerships with competitors. Originally, each of the company’s services was built to stand alone as a proprietary system. But that was then. Today, each Microsoft service is deeply interconnected to compound value across all of the company’s inhouse services. And Microsoft is vigorously opening up to collaborators of all types. Windows 11 now offers Amazon and Android app stores. Power Fx is now open source. Excel is programmable via Javascript. Microsoft Teams integrates with competing products like Slack. As for physical cities, the legacy structures may still serve as historical, charming artifacts, but value is clearly driven by the new metropolis that accelerates connectivity for the most ambitious builders and creators.

Microsoft’s results prove what was once considered impossible: that old folks can indeed breakdance. Microsoft may be one of the world’s largest company by market cap, but its recent results reflect the startup zeal with which it has been breaking walls. Overall revenue growth of 20% to $180bn annualized, over the last year, includes growth in customers of its leading security suite of more than 50% to nearly 650,000 customers. Power platform users, up 76% to 20mn, are beginning to see the emerging bridge between the hyperscale functionality of Azure and the easy interface of Excel. Within this, the low-code/no-code Power Apps workflow builder is growing revenues by 197%. Calls from chats within Microsoft Teams are up 50%. And large enterprises integrating with Teams are up 82%.

Every large company must now ask if its mindset and business model—like Microsoft’s—can defy the law of large numbers to fully realize its own growth potential. For example, Microsoft’s success puts pressure on Salesforce, which bought Slack to turbo-charge engagement within its enterprise customers and for better access to small and midsize businesses. Both Salesforce and Microsoft have joined Alibaba, Amazon, Google, Meta, and Tencent in showing one another how to build engagement across services while finely calibrating a personalized flywheel for each customer, creator, and business.

Re-Learning Rule #1: Coming Back Home to the First Customer

While experiencing the excitement of hyper-expansion across vast new territories, it is easy—even natural—to lose sight of the first customer. However, we believe the customer and competitive dynamics for each platform are reinforcing rule #1. For example, Alibaba has learned to match JD’s speedy delivery of electronic accessories and groceries for its initial customers in China’s megacities. While Alibaba deprioritized lower-quality goods several years ago, leaving an open door for Pinduoduo to walk through, the company has also relearned the need to reinvest in its original breadth of bargain offerings. Google is reviving its free-SEO spirit by finally enabling free listings in its shopping and travel vertical solutions. And perhaps the most vivid recent example is Meta renewing its attention on entertaining experiences for its original cohort of college students and young adults.

We also expect to make significant changes to Instagram and Facebook in the next year to further lean into video and make Reels a more central part of the experience. One aspect of this is giving all our apps the goal of being the best services for young adults, which we define as ages 18 to 29. Historically, young adults have been a strong base, and that’s important because they are the future. But over the last decade, as the audience that uses our apps has expanded so much and we focused on serving everyone, our services have gotten dialed to be the best for the most people who use them rather than specifically for young adults. And during this period, competition has also gotten a lot more intense, especially with Apple’s iMessage growing in popularity and, more recently, the rise of TikTok, which is one of the most effective competitors that we have ever faced.

— Mark Zuckerberg, founder-CEO of Meta Platforms, Q3’21 earnings call

As Meta learned from TikTok’s success, competitive dynamics will inevitably bring every company’s attention back home. Mark Zuckerberg, humbled both competitively and more broadly, is leveraging the company’s metaverse investments to enhance entertainment and shopping experiences on the company’s existing apps in the near term. Without this connection between long-term and near-term value for Meta’s original customers, we believe it would be difficult for the company to sustain its right to long-term growth.

I think you want to be able to have these experiences where you can feel present with people and have this immersive experience that’s going to be best if you’re in VR or in AR and your hologram, but it needs still to work everywhere, right? It needs to be able to work across our whole family of apps. It needs to be able to work on the web and on phones and on computers.

— Mark Zuckerberg, founder-CEO of Meta Platforms, Q3’21 earnings call

A Partnerships Renaissance: The Competitive need for Collaboration

He who sees all beings in his self and his self in all beings, loses all fear. How can the multiplicity of life delude the one who sees its unity?

— Isha Upanishad, The Upanishads, translated by Eknath Easwaran (Nilgiri Press, 2007)

As in other aspects of life, the law of karma assures not only individual benefit but also ecosystem health. We believe today’s competitive patterns are clear: the way to compete best is to partner best. This is perhaps the greatest reason for optimism—for the future of business, governance, society, and the world.

Does London’s growth really hurt New York? Or do they each benefit from helping build connections with each other? Some of the most competitive organizations have learned to embrace collaboration fully: even Amazon Essentials is now being advertised on Instagram and sold on Walmart.com!

The companies of the future see everyone as a partner, including governments and society at large. Given the breadth of their success, they understand that customers and society will demand that the most relevant companies also be better governed than governments in order to benefit society broadly. Can corporates even raise the governance bar to the point of inspiring governments to improve their own services to citizens?

In China, Alibaba and Tencent are stepping up investments to appease the government and go further in aligning fully with social needs. Alphabet, Meta, and Tencent are taking proactive steps to improve health and safety beyond any previous efforts of less pervasive media. Google Earth has been a powerful tool for environmentalists, while Amazon is actively marketing and recruiting for The Climate Pledge. Salesforce and Microsoft are building software for sustainability and backing social causes, including through Salesforce’s 1-1-1 commitment and Microsoft’s recent backing of social enterprises in India through Project Amplify. The emerging platforms are embracing social responsibility even earlier, with monday.com dedicating up to 10% of the company’s shares over ten years to its Equal Impact Initiative, aimed at aiding the digital transformation of nonprofits. Each of these businesses appreciates that its own broad relevance necessitates addressing social needs that were previously the realm of only government and social organizations.

We believe the age of customer obsession is great news for all of us. Our firm’s obsession with it reflects our deep conviction that investing in companies that we believe are the best at growing value for customers is the lowest-risk path to healthy returns for our partners. We are also delighted that natural, competitive forces are demanding so many companies to build collaborative metropolis ecosystems that create value for all stakeholders.

All streams flow to the sea because it is lower than they are. Humility gives it its power. If you want to govern the people, you must place yourself below them. If you want to lead the people, you must learn how to follow them.

— Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching, translated by Stephen Mitchell (Harper Perennial, 1994)